Subscribe to Our Insights

Thought Leadership

It’s the Spending, Stupid!

By Robert Kleinschmidt on June 6, 2011

James Carville is famous for having saved the first Clinton presidential campaign by focusing his candidate on the most important issue of the day. “It’s the Economy, Stupid,” ensured that the campaign stayed on point. Now there is a new most important issue of the day: out-of-control government spending. And the problem is getting worse.

To paraphrase Karl Marx’s famous line, a spectre is haunting America. It is the spectre of taxation: the idea that, in order to get out of our current economic dilemma, we must raise taxes to counter the spending spree we’ve been on. Specifically, we must raise taxes on the so-called wealthiest Americans, since they can shoulder the burden and, by giving up a greater share of their wealth, can save the country from government’s insatiable appetite to spend money.

It won’t work. It never has and it never will. All the data from the past 60 or so years show that the amount of taxes collected, as a per cent of GDP, is relatively constant regardless of the level of the top marginal rate, the rate paid by the “wealthy.” Why is this so? Part of the reason is the negative impact on the economy from higher rates, but the larger reason is that people react to the changes in top marginal rates, altering their income, investments, and behavior to reduce the tax bite. And it is the higher earners, particularly, who have the ability as well as the incentive to do so. This is not to say that governments will not try to fix their budget problems by raising tax rates. They most certainly will. And since Tocqueville is in the business of managing wealth for people, a discussion of this issue is important and timely.

First, let’s take a quick look at what’s been going on with the economy. Over the past 45 years, non-entitlement spending (including defense) has remained relatively constant as a percentage of GDP. Over the same time period, however, entitlement programs (Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid) have increased more than 1000 percent while real GDP has grown 300 percent. Entitlement programs were 6 percent of GDP in 1970; they now stand at 15 percent of GDP — and this before the baby-boom generation has reached retirement (and entitlement) age! Without any changes in policy, the numbers are going to get much worse.

At the state level, things look similarly grim. In 1945 there were 44 federal aid programs to the states totaling a few billion (2011) dollars. Last year’s programs totaled 1,122, paying out more than $600 billion. But to what avail? Unfunded state pension liabilities have grown steadily and now amount to trillions of dollars nationally.

And we all know about the impact that escalating healthcare costs are having on the economy. This country’s healthcare spending currently totals more than $2 trillion — higher than all other OECD countries combined. We’ve all seen the effect of this in the premiums we pay, either directly out of our pockets or as an increasingly onerous tax in our payroll checks.

Where is all this heading? Between 2030 and 2040, mandatory spending alone will exceed government revenues. And, somewhere around 2040, debt service will constitute the largest chunk of that spending.

What, if anything, is to be done? There is little disagreement on the need to restrain discretionary spending and, most critically, scale back the entitlement programs that constitute mandatory spending. Until we can come close to balancing the budget and reducing the debt we owe nationally and internationally, we’re in an out-of-control vehicle headed for a dangerous cliff.

However, there’s a sizeable percentage of Americans — a majority, according to some polls — that believes that we must also tax our way onto a safe road. But if you look at the facts, you see that this scheme just won’t work.

Let’s start with some numbers:

Over the twenty-year period from 1988 to 2007, the share of total income tax paid by the top 1 percent of earners rose by nearly fifty per cent from 27.5 per cent to 40.4 per cent. The share of taxes paid by the top 5 per cent rose from 45.6 to 60.6 per cent, a gain of approximately one-third. Meanwhile over the same period, the percentage of total adjusted gross income (AGI) earned by the top 1 per cent increased from 15.2 per cent to 22.8 per cent, a gain of fifty per cent; while for the group comprising the top 5% earners the share of AGI rose from 28.5 per cent of the total to 37.4 per cent, somewhat less than a third. These relationships hold true for the earners in the top 10 per cent and top 25 per cent category as well. Any way you look at it, the share of taxes on the top income earners have more than kept pace with the gain in their earnings; and, they are paying a far greater share of the income taxes collected than they were twenty years ago.

“But wait,” you might say, “shouldn’t those with more discretionary spending give even more than their fair share in taxes, in order to help the country balance its budget?” In another world, perhaps; but in this world, it just doesn’t work. From the end of World War II to today, the country’s revenue rate has remained steady at about 18 percent of GDP, despite the fact that the tax rate on the wealthiest Americans has ranged from less than 30 percent to more than 90 percent. And some studies have shown that, even if “the rich” paid all of their income in taxes — a 100-percent rate — the deficit would still be a trillion dollars.

The fact is that higher tax rates do not grow revenues, at least not by very much. Higher rates of taxation might mean more government programs, but not a stronger economy. Growth comes from innovation and productivity; from letting people and companies keep their money to spend on real goods and services; and from preventing entitlement programs from running out of control.

Should we lower marginal rates and simplify the tax code? Of course; but it is not in the interest of the political class to do so. It reduces their ability to extract funds in exchange for favors. Nor is it in the best interests of the lawyers and accountants, who make their living deciphering the code for their clients. And it certainly is not in the interests of the lobbyists, who grow fat from every government program and tax break. And don’t forget: All of these folks are important political contributors.

Meanwhile, what happens to people who suffer under the current tax code? The bottom line on taxes is that people will pay only so much before they begin to go loophole-hunting, and worse. What marginal tax rate triggers that behavior? I don’t know, but I think that we are very close to it right now.

So, where does that leave you and Tocqueville? From an investment point of view, as well as a wealth-preservation point of view, the attack on wealth-creation is a real thing and cannot be ignored. Lawyers and accountants play an important role in wealth preservation, but so do investment selection and allocation. Tax-exempt interest and low-dividend-paying growth stocks both become relatively more attractive in a higher-rate environment. Exposure to more-rapidly growing economies in countries more friendly to wealth and wealth creation also becomes more important. Domicile decisions, something we talk about with our clients, as well as trust arrangements, begin to play a larger role in countries hostile to wealth and its creation. We are becoming one of those, I fear.

That the clever and the connected tend to benefit the most from excessive government spending and regulation should come as no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention these past many years. Regrettably, that, too, needs to be taken into account in the investment process. It is no accident that General Electric is one of our largest positions, for example.

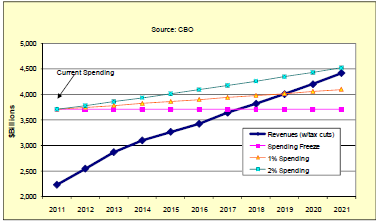

As grim as this all sounds, the outlook is not entirely without hope. In fact, because the trends are so negative and consequences so catastrophic, there is reason to believe that politicians might actually come together to address the budget issue. As the chart below shows, the budget could be put in balance, and relatively quickly, with simple spending restraint. This would be the most obvious, if politically difficult, solution, and it would be profoundly positive for the dollar, equities, and government bonds. As contrarian thinkers, we must not be oblivious to this possibility — but neither should we count on it.

The road that the U.S. economy finds itself on may be a rough one, but we at Tocqueville, with rigorous investment research, careful stock selection, and prudent asset allocation, will continue to try to smooth out the bumps as much as possible, all the while reminding our politicians, whenever the occasion permits, that it’s the spending, stupid!

Robert W. Kleinschmidt

June 6, 2011

This article reflects the views of the author as of the date or dates cited and may change at any time. The information should not be construed as investment advice. No representation is made concerning the accuracy of any cited data, nor is there any guarantee that any projection, forecast or opinion will be realized. We will periodically reprint charts or quote extensively from articles published by other sources. When we do, we will provide appropriate source information. The quotes and material that we reproduce are selected because, in our view, they provide an interesting, provocative or enlightening perspective on current events. Their reproduction in no way implies that we endorse any part of the material or investment recommendations published on those sites.

View PDFMutual Funds

You are about to leave the Private Wealth Management section of the website. The link you have accessed is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered a solicitation to become a shareholder of or invest in the Tocqueville Trust Mutual Funds. Please consider the investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses of any Mutual Fund carefully before investing. The prospectus contains this and other information about the Funds. You may obtain a free prospectus by downloading a copy from the Mutual Fund section of the website, by contacting an authorized broker/dealer, or by calling 1-800-697-3863.Please read the prospectus carefully before you invest. By accepting you will be leaving the Private Wealth Management section of the website.